- Home

- Louisa May Alcott

The Annotated Little Women Page 47

The Annotated Little Women Read online

Page 47

That had been one of her last “trifles,” and John’s eye had fallen on it as he spoke. “Oh, what will he say when he comes to that awful fifty dollars!” thought Meg, with a shiver.

“It’s worse than boots, it’s a silk dress,” she said, with the calmness of desperation, for she wanted the worst over.

“Well, dear, what is ‘the dem’d total?’ as Mr. Mantalini says.”8

That didn’t sound like John, and she knew he was looking up at her with the straightforward look that she had always been ready to meet and answer with one as frank, till now. She turned the page and her head at the same time, pointing to the sum which would have been bad enough without the fifty, but which was appalling to her with that added. For a minute the room was very still; then John said, slowly—but she could feel it cost him an effort to express no displeasure,—

“Well, I don’t know that fifty is much for a dress, with all the furbelows and quinny-dingles9 you have to have to finish it off these days.”

“It isn’t made or trimmed,” sighed Meg faintly, for a sudden recollection of the cost still to be incurred quite overwhelmed her.

“Twenty yards of silk seems a good deal to cover one small woman, but I’ve no doubt my wife will look as fine as Ned Moffat’s when she gets it on,” said John dryly.

“I know you are angry, John, but I can’t help it; I don’t mean to waste your money, and I didn’t think those little things would count up so. I can’t resist them when I see Sallie buying all she wants, and pitying me because I don’t; I try to be contented, but it is hard, and I’m tired of being poor.”

The last words were spoken so low she thought he did not hear them, but he did, and they wounded him deeply, for he had denied himself many pleasures for Meg’s sake. She could have bitten her tongue out the minute she had said it, for John pushed the books away and got up, saying, with a little quiver in his voice, “I was afraid of this; I do my best, Meg.” If he had scolded her, or even shaken her, it would not have broken her heart like those few words. She ran to him and held him close, crying, with repentant tears, “Oh, John! my dear, kind, hard-working boy, I didn’t mean it! It was so wicked, so untrue and ungrateful, how could I say it! Oh, how could I say it!”

He was very kind, forgave her readily, and did not utter one reproach; but Meg knew that she had done and said a thing which would not be forgotten soon, although he might never allude to it again. She had promised to love him for better for worse; and then she, his wife, had reproached him with his poverty, after spending his earnings recklessly. It was dreadful; and the worst of it was John went on so quietly afterward, just as if nothing had happened, except that he stayed in town later, and worked at night when she had gone to cry herself to sleep. A week of remorse nearly made Meg sick; and the discovery that John had countermanded the order for his new great-coat,10 reduced her to a state of despair which was pathetic to behold. He had simply said, in answer to her surprised inquiries as to the change, “I can’t afford it, my dear.”

Meg said no more, but a few minutes after he found her in the hall with her face buried in the old great-coat, crying as if her heart would break.

They had a long talk that night, and Meg learned to love her husband better for his poverty, because it seemed to have made a man of him—giving him the strength and courage to fight his own way—and taught him a tender patience with which to bear and comfort the natural longings and failures of those he loved.

Next day she put her pride in her pocket, went to Sallie, told the truth, and asked her to buy the silk as a favor. The good-natured Mrs. Moffat willingly did so, and had the delicacy not to make her a present of it immediately afterward. Then Meg ordered home the great-coat, and, when John arrived, she put it on, and asked him how he liked her new silk gown. One can imagine what answer he made, how he received his present, and what a blissful state of things ensued. John came home early, Meg gadded no more; and that great-coat was put on in the morning by a very happy husband, and taken off at night by a most devoted little wife. So the year rolled round, and at midsummer there came to Meg a new experience,—the deepest and tenderest of a woman’s life.

Laurie came creeping into the kitchen of the Dove-cote one Saturday, with an excited face, and was received with the clash of cymbals; for Hannah clapped her hands with a saucepan in one, and the cover in the other.

“How’s the little Ma? Where is everybody? Why didn’t you tell me before I came home?” began Laurie, in a loud whisper.

“Happy as a queen, the dear! Every soul of ’em is upstairs a worshipin’; we didn’t want no hurrycanes round. Now you go into the parlor, and I’ll send ’em down to you,” with which somewhat involved reply Hannah vanished, chuckling ecstatically.

Presently Jo appeared, proudly bearing a small flannel bundle laid forth upon a large pillow. Jo’s face was very sober, but her eyes twinkled, and there was an odd sound in her voice of repressed emotion of some sort.

“Shut your eyes and hold out your arms,” she said invitingly.

Laurie backed precipitately into a corner, and put his hands behind him with an imploring gesture,—“No, thank you; I’d rather not. I shall drop it, or smash it, as sure as fate.”

“Then you shan’t see your nevvy,” said Jo, decidedly, turning as if to go.

“I will, I will! only you must be responsible for damages;” and, obeying orders, Laurie heroically shut his eyes while something was put into his arms. A peal of laughter from Jo, Amy, Mrs. March, Hannah and John, caused him to open them the next minute, to find himself invested with two babies instead of one.11

No wonder they laughed, for the expression of his face was droll enough to convulse a Quaker, as he stood and stared wildly from the unconscious innocents to the hilarious spectators, with such dismay that Jo sat down on the floor and screamed.

“Twins, by Jupiter!” was all he said for a minute; then turning to the women with an appealing look that was comically piteous, he added, “Take ’em quick, somebody! I’m going to laugh, and I shall drop ’em.”

John rescued his babies, and marched up and down, with one on each arm, as if already initiated into the mysteries of baby-tending, while Laurie laughed till the tears ran down his cheeks.

Freddie (left) and Johnny Pratt. Alcott loved Anna’s children and envied her bliss. Referring to her stories, she told her journal, “I sell my children, and though they feed me, they don’t love me as hers do.” (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

“It’s the best joke of the season, isn’t it? I wouldn’t have you told, for I set my heart on surprising you, and I flatter myself I’ve done it,” said Jo, when she got her breath.

“I never was more staggered in my life. Isn’t it fun? Are they boys? What are you going to name them? Let’s have another look. Hold me up, Jo; for upon my life it’s one too many for me,” returned Laurie, regarding the infants with the air of a big, benevolent Newfoundland looking at a pair of infantile kittens.

“Boy and girl. Aren’t they beauties?” said the proud papa, beaming upon the little, red squirmers as if they were unfledged angels.

“Most remarkable children I ever saw. Which is which?” and Laurie bent like a well-sweep to examine the prodigies.

“Amy put a blue ribbon on the boy and a pink on the girl, French fashion, so you can always tell. Besides, one has blue eyes and one brown. Kiss them, Uncle Teddy,” said wicked Jo.

“I’m afraid they mightn’t like it,” began Laurie, with unusual timidity in such matters.

“Of course they will; they are used to it now; do it this minute, sir,” commanded Jo, fearing he might propose a proxy.

Laurie screwed up his face, and obeyed with a gingerly peck at each little cheek that produced another laugh, and made the babies squeal.

“There, I knew they didn’t like it! That’s the boy; see him kick! he hits out with his fists like a good one. Now then, young Brooke, pitch into a man of your own size, will you?” cried Laurie, delighted with a poke i

n the face from a tiny fist, flapping aimlessly about.

“He’s to be named John Laurence, and the girl Margaret, after mother and grandmother. We shall call her Daisy,12 so as not to have two Megs, and I suppose the mannie will be Jack, unless we find a better name,” said Amy, with aunt-like interest.

“Name him Demijohn,13 and call him ‘Demi’ for short,” said Laurie.

“Daisy and Demi,—just the thing! I knew Teddy would do it,” cried Jo, clapping her hands.

Teddy certainly had done it that time, for the babies were “Daisy” and “Demi” to the end of the chapter.

1. cumbered with many cares. In the Gospel According to Luke, Martha receives Jesus into her house. Whereas her sister, Mary, sits at Jesus’ feet and hears his word, Martha is “cumbered about much serving.” Annoyed that her sister is not helping, Martha asks Jesus to tell Mary to assist her. Jesus replies, “Martha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things, but one thing is needful: and Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:38–42).

2. very happy. John Bridge Pratt’s correspondence confirms that his marriage to Anna Alcott was blissful. He had “the best wife in the world, enough to live on economically, a pleasant boarding place and a contented heart” (Schlesinger, “The Alcotts through Thirty Years,” p. 378). Nevertheless, as the years passed, settling into work was not always easy for the patient, diligent Pratt. Early in the year he died, he complained, “A bookkeeper goes into the treadmill every day at a certain time and comes out at another certain hour and except that one day he wears a linen duster, and another a winter overcoat, one time is just like another. . . . I go round and round in the one beaten track so much and so long, that sometimes my head fairly swims, and I say ‘how long, oh Lord! How long’ ” (Schlesinger, “The Alcotts through Thirty Years,” p. 378).

A rare image of Anna Alcott Pratt. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

3. Mrs. Cornelius’s Receipt Book. Mary Hooker Cornelius wrote her book The Young Housekeeper’s Friend; or, A Guide to Domestic Economy and Comfort (ca. 1845) to “prevent very many of the perplexities which most young people suffer during their first years of married life.”

4. bread pudding Mrs. Cornelius offered this recipe for bread pudding:

Take nice pieces of light bread, break them up, and put a small pint bowl full into a quart of milk; set it in a tin pail or brown dish on the back part of the stove or range, where it will heat very gradually, and let it stand an hour or more. When the bread is soft enough to be made fine with a spoon, just boil it up; set it off, and stir in a large teaspoonful of butter, a little salt, and from two to four beaten eggs. Bake it an hour. Make a sauce for it. To be eaten without sauce, put in twice the measure of butter, beat the eggs with a cup of nice brown sugar, a teaspoonful of cinnamon, and half as much powdered clove. Add raisons [sic] if you like.

5. “I won’t have anything of the sort.” Meg might have done well to heed Mrs. Cornelius’s advice: “If you are subject to uninvited company, and your means do not allow you to set before your guests as good a table as they keep at home, do not distress yourself or them with apologies. If they are real friends, they will cheerfully sit down with you to such a table as is appropriate to your circumstances.”

6. Niobe. In Greek myth, Niobe haughtily boasts of her fourteen children to Zeus’s consort Leto, who has only two, Apollo and Artemis. In vengeance, Apollo and Artemis slaughter Niobe’s children. Niobe flees to Mount Sipylus and turns to stone but, despite her transformation, continues to cry without cease.

7. “piping” . . . “hug-me-tight.” Piping is a kind of trim or ornamentation, consisting of a strip of folded fabric inserted into a seam to define the edges or style lines of a garment. A hug-me-tight is a knitted, close-fitting jacket, typically without sleeves.

8. “Mr. Mantalini says.” Mr. Mantalini appears in Dickens’s The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39). He has a particular fondness for the word “dem’d.” Unlike John Brooke, who is a model of frugality, the spendthrift Mantalini lays waste to his wife’s finances and winds up in debtors’ prison.

9. “furbelows and quinny-dingles.” A furbelow is a flounce, ruffle, or superfluous decoration. “Quinny-dingle” seems to be a term of Alcott’s own coinage.

10. great-coat. A large, heavy overcoat.

11. two babies instead of one. Anna Alcott’s two children were not, like Demi and Daisy, fraternal twins of opposite sex, but rather two boys born from separate pregnancies. The older boy, Frederick Alcott Pratt, was born March 28, 1863. When Bronson brought the news of his birth to Orchard House, Abba, Louisa, and May “with one accord . . . opened our mouths & screamed for about two minutes; then mother began to cry, I to Laugh, & May to pour out questions, while Papa beamed upon us all . . . the image of a proud, old Grandpa” (Louisa May Alcott, Selected Letters, p. 83). Fred’s younger brother, John Sewall Pratt, was born June 24, 1865, “a fine little lad who took to life kindly & seemed to find the world all right” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 140). Though Anna and her husband were very pleased, they both had wished for a daughter (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 141). It amused John Sewall Pratt to write in later years, “I am ‘Daisy’ ” (Shealy, ed., Alcott in Her Own Time, p. 154).

12. “Daisy.” A common diminutive form of Margaret. See Part First, Chapter IX, Note 5.

13. “Demijohn.” A demijohn is a bulbous, narrow-necked bottle, holding anywhere from three to ten gallons. Laurie uses the word here to observe that John Laurence is a half-John, or a smaller version of his father.

CHAPTER VI.

Calls.1

“COME, Jo, it’s time.”

“For what?”

“You don’t mean to say you have forgotten that you promised to make half a dozen calls with me to-day?”

“I’ve done a good many rash and foolish things in my life, but I don’t think I ever was mad enough to say I’d make six calls in one day, when a single one upsets me for a week.”

“Yes you did; it was a bargain between us. I was to finish the crayon of Beth for you, and you were to go properly with me, and return our neighbors’ visits.”

“If it was fair—that was in the bond; and I stand to the letter of my bond, Shylock.2 There is a pile of clouds in the east; it’s not fair, and I don’t go.”

“Now that’s shirking. It’s a lovely day, no prospect of rain, and you pride yourself on keeping promises; so be honorable; come and do your duty, and then be at peace for another six months.”

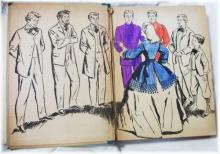

At that minute Jo was particularly absorbed in dressmaking; for she was mantua-maker general to the family, and took especial credit to herself because she could use a needle as well as a pen. It was very provoking to be arrested in the act of a first trying-on, and ordered out to make calls in her best array, on a warm July day. She hated calls of the formal sort, and never made any till Amy cornered her with a bargain, bribe, or promise. In the present instance, there was no escape; and having clashed her scissors rebelliously, while protesting that she smelt thunder, she gave in, put away her work, and taking up her hat and gloves with an air of resignation, told Amy the victim was ready.

“Jo March, you are perverse enough to provoke a saint! You don’t intend to make calls in that state, I hope,” cried Amy, surveying her with amazement.

“Why not? I’m neat, and cool, and comfortable; quite proper for a dusty walk on a warm day. If people care more for my clothes than they do for me, I don’t wish to see them. You can dress for both, and be as elegant as you please; it pays for you to be fine; it doesn’t for me, and furbelows only worry me.”

“Oh dear!” sighed Amy; “now she’s in a contrary fit, and will drive me distracted before I can get her properly ready. I’m sure it’s no pleasure to me to go to-day, but it’s a debt we owe society, and there’s no one to pay it but you and me. I’ll do anything for you, Jo, if you’ll only dress yourself nicely, and come and help me do the civil. You can talk so

well, look so aristocratic in your best things, and behave so beautifully, if you try, that I’m proud of you. I’m afraid to go alone; do come and take care of me.”

“You’re an artful little puss to flatter and wheedle your cross old sister in that way. The idea of my being aristocratic and well-bred, and your being afraid to go anywhere alone! I don’t know which is the most absurd. Well, I’ll go if I must, and do my best; you shall be commander of the expedition, and I’ll obey blindly; will that satisfy you?” said Jo, with a sudden change from perversity to lamb-like submission.

“You’re a perfect cherub! Now put on all your best things, and I’ll tell you how to behave at each place, so that you will make a good impression. I want people to like you, and they would if you’d only try to be a little more agreeable. Do your hair the pretty way, and put the pink rose in your bonnet; it’s becoming, and you look too sober in your plain suit. Take your light kids and the embroidered handkerchief. We’ll stop at Meg’s, and borrow her white sun-shade, and then you can have my dove-colored one.”

While Amy dressed, she issued her orders, and Jo obeyed them; not without entering her protest, however, for she sighed as she rustled into her new organdie,3 frowned darkly at herself as she tied her bonnet strings in an irreproachable bow, wrestled viciously with pins as she put on her collar, wrinkled up her features generally as she shook out the handkerchief, whose embroidery was as irritating to her nose as the present mission was to her feelings; and when she had squeezed her hands into tight gloves with two buttons and a tassel, as the last touch of elegance, she turned to Amy with an imbecile expression of countenance, saying meekly,—

“I’m perfectly miserable; but if you consider me presentable, I die happy.”

Little Women

Little Women Good Wives

Good Wives Jo's Boys

Jo's Boys Under the Lilacs

Under the Lilacs The Mysterious Key and What It Opened

The Mysterious Key and What It Opened The Inheritance

The Inheritance Eight Cousins

Eight Cousins Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill

Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill Marjorie's Three Gifts

Marjorie's Three Gifts Little Men

Little Men The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story

The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story Rose in Bloom

Rose in Bloom Shawl-Straps

Shawl-Straps Hospital Sketches

Hospital Sketches Flower Fables

Flower Fables An Old-Fashioned Girl

An Old-Fashioned Girl The Candy Country

The Candy Country Jack and Jill

Jack and Jill A Garland for Girls

A Garland for Girls The Annotated Little Women

The Annotated Little Women A Classic Christmas

A Classic Christmas A Merry Christmas

A Merry Christmas Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Little Vampire Women

Little Vampire Women