- Home

- Louisa May Alcott

The Annotated Little Women Page 4

The Annotated Little Women Read online

Page 4

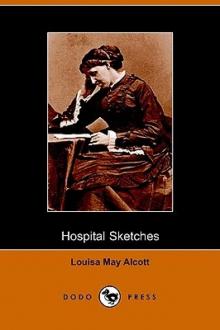

Alcott sat for this photograph, her most appealing likeness, in 1856, while the Alcotts were living in Walpole, New Hampshire. It closely resembles her description of Sylvia Yule, the heroine of her first published novel, Moods: a face “full of contradictions,—youthful, maidenly, and intelligent, yet touched with the unconscious melancholy that is born of disappointment and desire.” (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

1 There is, unfortunately, no way of knowing whether or to what extent Niles revised Alcott’s first twelve chapters once he realized that he might have a hit on his hands.

2 Louisa May Alcott to Elizabeth Powell, March 20, 1869, The Selected Letters of Louisa May Alcott, p. 125.

“We Really Lived Most of It”: A Biographical Note

IN a letter that she sent to her editor Thomas Niles soon before the first volume of Little Women was published, Louisa May Alcott wrote, “I don’t care for a Preface.”1 Thus, the present edition of the novel begins by violating its author’s intentions. We should not be overly troubled by this fact, however, since the writing of Little Women itself did not fit in easily with Alcott’s personal desires or expectations. It was a book that she wrote only with considerable reluctance, and it ends far differently from the way she initially conceived. Alcott was prone to observe that everything went “by contraries” with her, and Little Women is, indeed, arguably one of the most paradoxical books in the American canon. Whereas Alcott herself resisted the constraints of conventional femininity, Little Women was held up for generations as a model for young female behavior. Although she grew up among the Transcendentalist avatars of self-reliance, Alcott crafted in her fiction an ideal vision of interdependence. She raised her family out of its chronic indebtedness by publishing fiction that celebrated the virtues of genteel poverty. Both in the circumstances of its creation and in its consideration of the questions of family, womanhood, and moral growth that lie at its core, Little Women is a book supremely rich in surprises. No one was more surprised by Little Women than Louisa May Alcott herself. When Alcott set herself to writing the manuscript, she had no idea that she was about to author an enduring children’s classic, and neither did she imagine that her book would one day be regarded as a pioneering work in the then-nascent movement of American literary realism.

Nevertheless, few readers who come—and come back—to Little Women are looking to be surprised. They come instead seeking assurance. They look for and find a promise that life’s hardships, whether they may take the form of poverty, a family divided by distance and war, or the petty demons that one must subdue within one’s own nature, can be endured and surmounted. And they wish to be reminded that the battle can be won with defenses no more sophisticated than a resolute heart and a loving family. It is not always clear in Little Women that the armor will be thick enough. What reader cannot relate her or his own experience to the fears of Beth, when she timorously ventures into the lair of the imperious Mr. Laurence, or to the inner agonies of Jo as she gradually realizes that she must leave childhood behind and make a name for herself in a large and highly indifferent world? One sympathizes instinctively with the awkwardness of Meg as she is thrust forward into social circles that she hardly comprehends, as well as with Amy’s sense of disgrace when her much-awaited luncheon with her fashionable but fickle drawing class dissolves into a social catastrophe. In all these situations, the easier path would be to run away and avoid the consequences. But running away too often or for too long is seldom realistic, and it is to Little Women’s realism that readers have eagerly responded since the novel first appeared—the first part in 1868 and the second in 1869. Alcott herself believed the story was so good because it was “not a bit sensational, but simple and true”; in her words, “We really lived most of it, and if it succeeds that will be the reason of it.”2

Some have challenged Alcott’s assessment of her book’s verisimilitude. They observe that Alcott’s own youth was marred by deeper poverty and tinged with darker emotional tones than the adventures of the March sisters. Nevertheless, compared with much of what preceded it in American popular fiction—and certainly in comparison with earlier books for children and adolescents—Little Women is remarkable for its lack of supernaturalism and fantasy. In calling her book a realistic work, Alcott was much more right than wrong. Even in those parts that Alcott was forced to draw from her rich imagination, Little Women feels imbued with the essences of life and truth.

Although a flavor of autobiography has animated many great works of American fiction, it is hard to think of a classic American novel that is more deeply rooted in actual lived experience than Little Women. Because this is so, the life of the author takes on particular importance. It is not possible truly to know Little Women without getting to know Louisa May Alcott.

A person who came to Concord, Massachusetts, in December 1847 might have met Louisa May Alcott at fifteen, the same age that Alcott’s alter ego Jo March has achieved at the start of Little Women. Such a visitor would have encountered a young woman of athletic skill and startling vitality. No boy could be her friend, Alcott later wrote, until she had beaten him in a footrace, and no girl could win her affections “if she refused to climb trees, leap fences and be a tomboy.”3 With her clear, olive-brown complexion and brown hair and eyes, Alcott suited perfectly what a close friend called “an ideal of the ‘Nut Brown Maid’; she was full of spirit and life; impulsive and moody, and at times irritable and nervous.” The friend went on to observe, “She could run like a gazelle. She was the most beautiful girl runner I ever saw. She . . . dearly loved a good romp.”4 Another acquaintance of Alcott’s youth particularly remembered her face. With its cheeks “glowing with the flush that amusement or vexation brought to them,” it was “a most pleasing one to look upon.”5 Alcott’s physical vitality carried over fully into her character, and it was a force that she found extremely hard to control. Even in the memory of her highly forgiving older sister, Anna, she “was a dreadful girl, always full of wild pranks.”6 Others found her “a strange and unpredictable creature, full of . . . moods, impulsive and loving and fretted always by the restraint of being a young lady, not a boy.”7 It is probably no great coincidence that that three of the observers just quoted remembered the young Alcott as being “full” of one thing or another. There was within her, it seems, a certain overflowing quality, a superabundance of emotion and energy that her spare, athletic body could barely contain.

If that same visitor were to have encountered Alcott again twenty-one years later, in the year when she wrote Little Women, she or he might have been sobered by the tremendous change that its author had undergone. To a fan who later wrote to ask her what was the easy road to success as a writer, Alcott replied that there was none. As she herself retold it, Alcott had “worked for twenty years poorly paid, little known, & quite without any ambition but to eke out a living, as I chose to support myself & began to do it at sixteen.”8 The hard work alone would have stolen some of the bloom from Alcott’s cheeks, but she had suffered through a frightful illness as well. In January 1863, while serving her country as an army nurse during the Civil War, Alcott contracted typhoid pneumonia at the hospital where she was on duty. Her doctors had worsened the situation by giving her large doses of calomel. The medicine, a mercury compound, lodged in her system and nearly killed her. Alcott suffered the effects of mercury poisoning for the remainder of her life. The symptoms came and went; at times she felt well, but at others she struggled against an “invalidism that I hate worse than death.”9 Her former healthy, brimming fullness never entirely returned. Commenting on portraits made of her after her illness, she observed, “When I don’t look like the tragic muse, I look like a smoky relic of the great Boston fire.”10 Once Little Women had made her and her family famous, people flocked to Concord “to come and stare at the Alcotts.”11 It saddened her that so many visitors came in expectation of seeing the perennially young “topsey turvey” Jo March of Little Women, only to find instead “a tired out old lady.”12 Despi

te the wearying effects of time and illness, however, the spirit fought to remain essentially unaltered. Alcott wrote, “In spite of age, much work, and the proprieties, an occasional fit of the old jollity comes over me, and I find I have not forgotten how to romp as in my Joian days.”13

Illness and overwork nearly killed Alcott during her nursing service at the Union Hotel Hospital in 1862–63. However, her trials taught her the value of writing about realistic subjects and led to her first great publishing success, Hospital Sketches. (Library of Congress)

One comes to the author of Little Women, then, with a choice of Alcotts: the boisterous young woman with a tremendous love of fun and an equally prodigious temper, or the successful, matronly author, still generous and good-humored but old before her time. The choice becomes more complicated when one reads the letters and journals of the grown woman side by side. The letters, while they freely acknowledge Alcott’s difficulties, are typically buoyant in tone. The journals, in which Alcott felt no obligation to perform or otherwise maintain appearances, are correspondingly darker, revealing a woman inwardly soured by chronic illness and frustrated with having neither the health nor the time to attempt the books for adult audiences that she wanted to write.

A three-quarters view of Louisa May Alcott. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Ironically for an author whose work so frequently celebrates the blessings of domestic life, much of the force that wore Alcott down at such an early age came from within her own family. A man with deep contempt for most worldly occupations, Louisa’s father, Bronson, made a modest living during Louisa’s early childhood as a schoolmaster. When Louisa was not yet seven, however, Bronson’s controversial teaching methods and progressive opinions (he enrolled a black child in his Boston school, prompting an exodus of white families) brought an abrupt and bruising end to his career. Thereafter, he earned money sporadically by giving public conversations and performing agricultural labor. However, from the time Louisa was six until she was twenty-six, her father had no steady income. Beginning in her teens, Louisa worked to help supply her parents and sisters with necessities that her father could not afford. Louisa’s early-acquired habits of self-sacrifice for her family persisted until her death. In later years she subsidized her nephews’ education as well as her younger sister May’s artistic training and European travels. When May unexpectedly died, leaving a baby girl, Louisa became the infant’s guardian. At fifty-five, Alcott wrote, “As I don’t live for myself I hold on for others, & shall find time to die some day, I hope.”14 Only two days later, that time found her.

A trusting, optimistic expression illuminates this early portrait of Bronson Alcott.

Yet the family that seemed forever to be holding Alcott back also gave her life much of its direction and meaning. The encouragement and guidance of her mother, the admiration of her siblings, and the indefatigable optimism of her father buoyed her up as much as their many dependencies weighed her down. They also provided Alcott with her great, defining subject: the delicate but durable strands of emotion and experience that join parent to child and sibling to sibling. Through and with her family, Alcott experienced the moments of sorrow, anger, frustration, and hard-won joy that she was to transform into her greatest fiction.

The life that spawned the fiction began on November 29, 1832; Louisa May Alcott was born on her father’s thirty-third birthday. Her elder sister Anna was then twenty months old. Two younger sisters—Elizabeth, known in the family as Lizzie, and Abigail, who preferred her middle name May—joined the family in 1835 and 1840. Germantown, Pennsylvania, Alcott’s birthplace, was little more than a way station for the Alcott family, though the same might be said of many of Louisa’s transitory childhood homes. Always seeking the ideal environment and often unable to pay for the places he found, Bronson Alcott moved his family dozens of times during Louisa’s childhood. Louisa’s first years were some of Bronson’s most prosperous. When Louisa was not yet three, he established a school in Boston’s Masonic Temple, where his novel approach to teaching made him, for a time, the toast of liberal New England. Believing that children possessed a unique wisdom, the elder Alcott asked his pupils as many questions as he gave answers. Challenging even very young children to think deeply about the workings of their minds and the nature of the moral universe, Bronson grasped the importance of educating the whole child—not only the intellect, but also the body and the spirit. The principles that he introduced in his school, Alcott sought to perfect in his own children’s nursery. He sought to rid his home of harsh stimuli and angry sentiments, filling it with sights and sounds that would reward his daughters’ curiosity and instill in them a love of peace and harmony. From the day that Anna and Louisa were born, Bronson, who was a compulsive diarist in his own right, kept separate journals in which he recorded every observable fact of the two girls’ development. Through these records, which eventually filled hundreds of pages, he hoped to unlock the secrets of the infant mind. He also hoped, once the girls were old enough to write for themselves, to have them continue the project through their lives, thus creating comprehensive histories of their minds from cradle to grave. Though Bronson’s scientific passion eventually cooled, the Alcott girls experienced highly scrutinized childhoods, ones marked by both careful moral restraint and aesthetic indulgence. When the guests at her birthday party outnumbered by one the available slices of cake, Louisa was required to relinquish hers to the supernumerary visitor. By contrast, when younger sister May displayed artistic talent, her parents permitted her to draw on the walls of her room. Both the strictness and the permissiveness were calculated to produce morally and intellectually exceptional children.

The Temple School in Boston, the scene of Bronson Alcott’s brightest fame—and his most crushing scandal. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

With Louisa, Bronson feared he had failed. Instead of the gentle, even-tempered girl he had hoped to create, Louisa was a willful and assertive tomboy, prone to outbursts of temper and open to every kind of innocent mischief. To all her father’s cherished theories of child rearing, she seemed the walking refutation. Despairing over her waywardness, Bronson chided the ten-year-old Louisa for her “anger, discontent, impatience [and] greedy wants.”15 For solace and encouragement, Louisa turned toward her mother, Abba, who praised her early poems as the work of a budding Shakespeare and who saw strength where her husband saw only stubbornness. “I believe,” she wrote, “there are some natures too noble to curb, too lofty to bend. Of such is my Lu.”16 For her part, Louisa thought her mother “the best woman in the world.”17

Poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) led the American Transcendentalist movement. Louisa considered him “the man who has helped me most by his life, his books, his society. I can never tell all he has been to me.” The autographed poem reads “Well and wisely said the Greek, / Be thou faithful but not fond; / To the altar’s foot thy fellow seek, / The Furies wait beyond.” (From the collection of the editor)

The Alcotts settled in Concord not once but three times: from 1840 to 1843, then from 1845 to 1848, and finally in 1857. In 1858, they moved into the home Bronson christened Orchard House, where they remained until 1877. It was in Concord that Louisa came to know her father’s close friends Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as a somewhat less warm acquaintance, Nathaniel Hawthorne. Emerson shared his library with Louisa. Thoreau took her and her sisters on nature walks and boating expeditions. It was a girlhood of intellectual riches. It was also an early life of grinding poverty. Convinced of the evil of the moneymaking world, Bronson intended, by his Spartan example, to persuade his daughters of the unimportance of money. To the contrary, a long history of meager meals and patched clothing taught Louisa that money mattered very much indeed. She taught; she sewed; she hired herself out for housework—anything to bring in an extra dollar. From the age of eighteen, she noted in her journal every scrap of income that came her way. Even after the success of Little Women brought her

all the money she had ever imagined, she would drive herself relentlessly to write for pay. In her mind, made all too sensitive by early deprivations, no amount of security was ever enough.

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), the author of Walden and “Civil Disobedience,” showed Alcott the sanctity of the natural world. When he died, she wrote, “Though he didn’t go to church he was a better Christian than many who did.” (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Perhaps the defining episode of Alcott’s childhood began with high hopes on an overcast day in June 1843 and ended the following January in snow and shattered hopes. The seven-month interval in between witnessed the rise, decline, and fall of her father’s boldest social experiment, the communal farm he called Fruitlands. The idea for Fruitlands first came to Alcott on a visit to England in 1842. With encouragement and a financial subsidy from Emerson, he had gone at the invitation of a group of reformers who were so taken with the American’s educational theories that they had christened their experimental school “Alcott House.” While there, Bronson forged a friendship with Charles Lane, a disaffected financial journalist who had concluded that the existing society had become all but hopeless in its moral corruption. Together with Henry Wright, another visionary at Alcott House, Bronson and Lane conceived of a “new plantation in America” that would undo society’s wrongs and supply a model for the world’s renewal.18 The community would do away with money and private property. It would also rigorously exclude any products that, like cotton and sugar, were produced by slave labor. Though these ideas were radical enough in the 1840s, Alcott and his friends extended their moral purity further still. They and their followers would also benefit their animal brethren by abstaining from consuming meat, fish, milk, and eggs and by shunning all other animal products as well: they would abide no silk, no woolen garments, no leather in their shoes. To many, the reformers’ extremism seemed laughable. Yet it was hard to justly criticize the purity of their goal: to live life in a way that caused no pain to any living creature.

Little Women

Little Women Good Wives

Good Wives Jo's Boys

Jo's Boys Under the Lilacs

Under the Lilacs The Mysterious Key and What It Opened

The Mysterious Key and What It Opened The Inheritance

The Inheritance Eight Cousins

Eight Cousins Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill

Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill Marjorie's Three Gifts

Marjorie's Three Gifts Little Men

Little Men The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story

The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story Rose in Bloom

Rose in Bloom Shawl-Straps

Shawl-Straps Hospital Sketches

Hospital Sketches Flower Fables

Flower Fables An Old-Fashioned Girl

An Old-Fashioned Girl The Candy Country

The Candy Country Jack and Jill

Jack and Jill A Garland for Girls

A Garland for Girls The Annotated Little Women

The Annotated Little Women A Classic Christmas

A Classic Christmas A Merry Christmas

A Merry Christmas Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Little Vampire Women

Little Vampire Women