- Home

- Louisa May Alcott

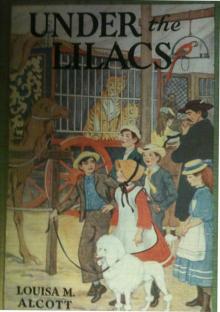

Under the Lilacs Page 23

Under the Lilacs Read online

Page 23

CHAPTER XXIII

SOMEBODY COMES

Bab and Betty had been playing in the avenue all the afternoon severalweeks later, but as the shadows began to lengthen both agreed to situpon the gate and rest while waiting for Ben, who had gone nutting witha party of boys. When they played house Bab was always the father, andwent hunting or fishing with great energy and success, bringing home allsorts of game, from elephants and crocodiles to humming-birds andminnows. Betty was the mother, and a most notable little housewife,always mixing up imaginary delicacies with sand and dirt in old pans andbroken china, which she baked in an oven of her own construction.

Both had worked hard that day, and were glad to retire to their favoritelounging-place, where Bab was happy trying to walk across the wide topbar without falling off, and Betty enjoyed slow, luxurious swings whileher sister was recovering from her tumbles. On this occasion, havingindulged their respective tastes, they paused for a brief interval ofconversation, sitting side by side on the gate like a pair of plump graychickens gone to roost.

"Don't you hope Ben will get his bag full? We shall have such funeating nuts evenings observed Bab, wrapping her arms in her apron, forit was October now, and the air was growing keen.

"Yes, and Ma says we may boil some in our little kettles. Ben promisedwe should have half," answered Betty, still intent on her cookery.

"I shall save some of mine for Thorny."

"I shall keep lots of mine for Miss Celia."

"Doesn't it seem more than two weeks since she went away?"

"I wonder what she'll bring us."

Before Bab could conjecture, the sound of a step and a familiar whistlemade both look expectantly toward the turn in the road, all ready to cryout in one voice, "How many have you got?" Neither spoke a word,however, for the figure which presently appeared was not Ben, but astranger,--a man who stopped whistling, and came slowly on dusting hisshoes in the way-side grass, and brushing the sleeves of his shabbyvelveteen coat as if anxious to freshen himself up a bit.

"It's a tramp, let's run away," whispered Betty, after a hasty look.

"I ain't afraid," and Bab was about to assume her boldest look when asneeze spoilt it, and made her clutch the gate to hold on.

At that unexpected sound the man looked up, showing a thin, dark face,with a pair of sharp, black eyes, which surveyed the little girls sosteadily that Betty quaked, and Bab began to wish she had at leastjumped down inside the gate.

"How are you?" said the man with a goodnatured nod and smile, as if tore-assure the round-eyed children staring at him.

"Pretty well, thank you, sir," responded Bab, politely nodding back athim.

"Folks at home?" asked the man, looking over their heads toward thehouse.

"Only Ma; all the rest have gone to be married."

"That sounds lively. At the other place all the folks had gone to afuneral," and the man laughed as he glanced at the big house on thehill.

"Why, do you know the Squire?" exclaimed Bab, much surprised andre-assured.

"Come on purpose to see him. Just strolling round till he gets back,"with an impatient sort of sigh.

"Betty thought you was a tramp, but I wasn't afraid. I like tramps eversince Ben came," explained Bab, with her usual candor.

"Who 's Ben!" and the man came nearer so quickly that Betty nearly fellbackward. "Don't you be scared, Sissy. I like little girls, so you seteasy and tell me about Ben," he added, in a persuasive tone, as heleaned on the gate so near that both could see what a friendly face hehad in spite of its eager, anxious look.

"Ben is Miss Celia's boy. We found him most starved in the coach-house,and he's been here ever since," answered Bab, comprehensively.

"Tell me about it. I like tramps, too," and the man looked as if he didvery much, as Bab told the little story in a few childish words thatwere better than a much more elegant account.

"You were very good to the little feller," was all the man said when sheended her somewhat confused tale, in which she had jumbled the old coachand Miss Celia, dinner-pails and nutting, Sancho and circuses.

"'Course we were! He's a nice boy and we are fond of him, and he likesus," said Bab, heartily.

"'Specially me," put in Betty, quite at ease now, for the black eyeshad softened wonderfully, and the brown face was smiling all over.

"Don't wonder a mite. You are the nicest pair of little girls I've seenthis long time," and the man put a hand on either side of them, as if hewanted to hug the chubby children. But he didn't do it; he merely smiledand stood there asking questions till the two chatterboxes had told himevery thing there was to tell in the most confiding manner, for he verysoon ceased to seem like a stranger, and looked so familiar that Bab,growing inquisitive in her turn, suddenly said,--

"Haven't you ever been here before? It seems as if I'd seen you."

"Never in my life. Guess you've seen somebody that looks like me," andthe black eyes twinkled for a minute as they looked into the puzzledlittle faces before him, then he said, soberly,--

"I'm looking round for a likely boy; don't you think this Ben wouldsuite me? I want just such a lively sort of chap."

"Are you a circus man?" asked Bab, quickly.

"Well, no, not now. I'm in better business."

"I'm glad of it--we don't approve of 'em; but I do think they'resplendid!"

Bab began by gravely quoting Miss Celia, and ended with an irrepressibleburst of admiration which contrasted drolly with her first remark.

Betty added, anxiously: "We can't let Ben go any way. I know hewouldn't want to, and Miss Celia would feel bad. Please don't ask him."

"He can do as he likes, I suppose. He hasn't got any folks of his own,has he?"

"No, his father died in California, and Ben felt so bad he cried, and wewere real sorry, and gave him a piece of Ma, 'cause he was so lonesome,"answered Betty, in her tender little voice, with a pleading look whichmade the man stroke her smooth check and say, quite softly,--

"Bless your heart for that! I won't take him away, child, or do a thingto trouble anybody that's been good to him."

"He 's coming now. I hear Sanch barking at the squirrels!" cried Bab,standing up to get a good look down the road.

The man turned quickly, and Betty saw that he breathed fast as hewatched the spot where the low sunshine lay warmly on the red maple atthe corner. Into this glow came unconscious Ben, whistling "RoryO'Moore," loud and Clear, as he trudged along with a heavy bag of nutsover his shoulder and the light full on his contented face. Sanchotrotted before and saw the stranger first, for the sun in Ben's eyesdazzled him. Since his sad loss Sancho cherished a strong dislike totramps, and now he paused to growl and show his teeth, evidentlyintending to warn this one off the premises.

"He won't hurt you--" began Bab, encouragingly; but before she couldadd a chiding word to the dog, Sanch gave an excited howl, and flew atthe man's throat as if about to throttle him.

Betty screamed, and Bab was about to go to the rescue when bothperceived that the dog was licking the stranger's face in an ecstasy ofjoy, and heard the man say as he hugged the curly beast,--

"Good old Sanch! I knew he wouldn't forget master, and he doesn't."

"What's the matter?" called Ben, coming up briskly, with a strong gripof his stout stick. There was no need of any answer, for, as he cameinto the shadow, he saw the man, and stood looking at him as if he werea ghost.

"It's father, Benny; don't you know me?" asked the man, with an odd sortof choke in his voice, as he thrust the dog away, and held out bothhands to the boy. Down dropped the nuts, and crying, "Oh, Daddy, Daddy!"Ben cast himself into the arms of the shabby velveteen coat, while poorSanch tore round them in distracted circles, barking wildly, as if thatwas the only way in which he could vent his rapture.

What happened next Bab and Betty never stopped to see, but, droppingfrom their roost, they went flying home like startled Chicken Littleswith the astounding news that "Ben's father has come alive, and Sanchoknew him right away!"<

br />

Mrs. Moss had just got her cleaning done up, and was resting a minutebefore setting the table, but she flew out of her old rocking-chair whenthe excited children told the wonderful tale, exclaiming as they ended,--

"Where is he? Go bring him here. I declare it fairly takes my breathaway!"

Before Bab could obey, or her mother compose herself, Sancho bounced inand spun round like an insane top, trying to stand on his head, walkupright, waltz and bark all at once, for the good old fellow had so losthis head that he forgot the loss of his tail.

"They are coming! they are coming! See, Ma, what a nice man he is," saidBab, hopping about on one foot as she watched the slowly approachingpair.

"My patience, don't they look alike! I should know he was Ben's Paanywhere!" said Mrs. Moss, running to the door in a hurry.

They certainly did resemble one another, and it was almost comical tosee the same curve in the legs, the same wide-awake style of wearing thehat, the same sparkle of the eye, good-natured smile and agile motion ofevery limb. Old Ben carried the bag in one hand while young Ben held theother fast, looking a little shame-faced at his own emotion now, forthere were marks of tears on his cheeks, but too glad to repress thedelight he felt that he had really found Daddy this side heaven.

Mrs. Moss unconsciously made a pretty little picture of herself as shestood at the door with her honest face shining and both hands ont,saying in a hearty tone, which was a welcome in itself,

"I'm real glad to see you safe and well, Mr. Brown! Come right in andmake yourself to home. I guess there isn't a happier boy living than Benis to-night."

"And I know there isn't a gratefuler man living than I am for yourkindness to my poor forsaken little feller," answered Mr. Brown,dropping both his burdens to give the comely woman's hands a hard shake.

"Now don't say a word about it, but sit down and rest, and we'll havetea in less'n no time. Ben must be tired and hungry, though he's sohappy I don't believe he knows it," laughed Mrs. Moss, bustling away tohide the tears in her eyes, anxious to make things sociable and easy allround.

With this end in view she set forth her best china, and covered thetable with food enough for a dozen, thanking her stars that it wasbaking day, and every thing had turned out well. Ben and his father sattalking by the window till they were bidden to "draw up and helpthemselves" with such hospitable warmth that every thing had an extrarelish to the hungry pair.

Ben paused occasionally to stroke the rusty coat-sleeve withbread-and-buttery fingers to convince himself that "Daddy" had reallycome, and his father disposed of various inconvenient emotions by eatingas if food was unknown in California. Mrs. Moss beamed on every one frombehind the big tea-pot like a mild full moon, while Bab and Betty keptinterrupting one another in their eagerness to tell something new aboutBen and how Sanch lost his tail.

"Now you let Mr. Brown talk a little; we all want to hear how he 'camealive,' as you call it," said Mrs. Moss, as they drew round the fire inthe "settin'-room," leaving the tea-things to take care of themselves.

It was not a long story, but a very interesting one to this circle oflisteners; all about the wild life on the plains trading for mustangs,the terrible kick from a vicious horse that nearly killed Ben, sen., thelong months of unconsciousness in the California hospital, the slowrecovery, the journey back, Mr. Smithers's tale of the boy'sdisappearance, and then the anxious trip to find out from Squire Allenwhere he now was.

"I asked the hospital folks to write and tell you as soon as I knewwhether I was on my head or my heels, and they promised; but theydidn't; so I came off the minute I could, and worked my way back,expecting to find you at the old place. I was afraid you'd have worn outyour welcome here and gone off again, for you are as fond of travellingas your father."

"I wanted to sometimes, but the folks here were so dreadful good to me Icouldn't," confessed Ben, secretly surprised to find that the prospectof going off with Daddy even cost him a pang of regret, for the boy hadtaken root in the friendly soil, and was no longer a wanderingthistle-down, tossed about by every wind that blew.

"I know what I owe 'em, and you and I will work out that debt before wedie, or our name isn't B.B.," said Mr. Brown, with an emphatic slap onhis knee, which Ben imitated half unconsciously as he exclaimedheartily,--

"That's so!" adding, more quietly, "What are you going to do now? Goback to Smithers and the old business?"

"Not likely, after the way he treated you, Sonny. I've had it out withhim, and he won't want to see me again in a hurry," answered Mr. Brown,with a sudden kindling of the eye that reminded Bab of Ben's face whenhe shook her after losing Sancho.

"There's more circuses than his in the world; but I'll have to limberout ever so much before I'm good for much in that line," said the boy,stretching his stout arms and legs with a curious mixture ofsatisfaction and regret.

"You've been living in clover and got fat, you rascal," and his fathergave him a poke here and there, as Mr. Squeers did the plump Wackford,when displaying him as a specimen of the fine diet at Do-the-boys Hall."Don't believe I could put you up now if I tried, for I haven't got mystrength back yet, and we are both out of practice. It's just as well,for I've about made up my mind to quit the business and settle downsomewhere for a spell, if I can get any thing to do," continued therider, folding his arms and gazing thoughtfully into the fire.

"I shouldn't wonder a mite if you could right here, for Mr. Towne has agreat boarding-stable over yonder, and he's always wanting men." SaidMrs. Moss, eagerly, for she dreaded to have Ben go, and no one couldforbid it if his father chose to take him away.

"That sounds likely. Thanky, ma'am. I'll look up the concern and trymy chance. Would you call it too great a come-down to have father an'ostler after being first rider in the 'Great Golden Menagerie, Circus,and Colossem,' hey, Ben?" asked Mr. Brown, quoting the well-rememberedshow-bill with a laugh.

"No, I shouldn't; it's real jolly up there when the big barn is full andeighty horses have to be taken care of. I love to go and see 'em. Mr.Towne asked me to come and be stable-boy when I rode the kicking graythe rest were afraid of. I hankered to go, but Miss Celia had just gotmy new books, and I knew she'd feel bad if I gave up going to school.Now I'm glad I didn't, for I get on first rate and like it."

"You done right, boy, and I'm pleased with you. Don't you ever beungrateful to them that befriended you, if you want to prosper. I'lltackle the stable business a Monday and see what's to be done. Now Iought to be walking, but I'll be round in the morning ma'am, if you canspare Ben for a spell to-morrow. We'd like to have a good Sunday trampand talk; wouldn't we, Sonny?" and Mr. Brown rose to go with his hand onBen's shoulder, as if loth to leave him even for the night.

Mrs. Moss saw the longing in his face, and forgetting that he was anutter stranger, spoke right out of her hospitable heart.

"It's a long piece to the tavern, and my little back bedroom is alwaysready. It won't make a mite of trouble if you don't mind a plain place,and you are heartily welcome."

Mr. Brown looked pleased, but hesitated to accept any further favor fromthe good soul who had already done so much for him and his. Ben gave himno time to speak, however, for running to a door he flung it open andbeckoned, saying, eagerly,--

"Do stay, father; it will be so nice to have you. This is a tip-toproom; I slept here the night I came, and that bed was just splendidafter bare ground for a fortnight."

"I'll stop, and as I'm pretty well done up, I guess we may as well turnin now," answered the new guest; then, as if the memory of that homelesslittle lad so kindly cherished made his heart overflow in spite of him,Mr. Brown paused at the door to say hastily, with a hand on Bab andBetty's heads, as if his promise was a very earnest one,--

"I don't forget, ma'am, these children shall never want a friend whileBen Brown's alive;" then he shut the door so quickly that the otherBen's prompt "Hear, hear!" was cut short in the middle.

"I s'pose he means that we shall have a piece of Ben's father, becausewe gave Ben a piece

of our mother," said Betty, softly.

"Of course he does, and it's all fair," answered Bab, decidedly. "Isn'the a nice man, Ma?

"Go to bed, children," was all the answer she got; but when they weregone, Mrs. Moss, as she washed up her dishes, more than once glanced ata certain nail where a man's hat had not hung for five years, andthought with a sigh what a natural, protecting air that slouched felthad.

If one wedding were not quite enough for a child's story, we might herehint what no one dreamed of then, that before the year came round againBen had found a mother, Bab and Betty a father, and Mr. Brown's hat wasquite at home behind the kitchen door. But, on the whole, it is best notto say a word about it.

CHAPTER XXIV

THE GREAT GATE IS OPENED

The Browns were up and out so early next morning that Bab and Betty weresure they had run away in the night. But on looking for them, they werediscovered in the coach-house criticising Lita, both with their hands intheir pockets, both chewing straws, and looking as much alike as a bigelephant and a small one.

"That's as pretty a little span as I've seen for a long time," said theelder Ben, as the children came trotting down the path hand in hand,with the four blue bows at the ends of their braids bobbing briskly upand down.

"The nigh one is my favorite, but the off one is the best goer, thoughshe's dreadfully hard bitted," answered Ben the younger, with such acomical assumption of a jockey's important air that his father laughedas he said in an undertone,--

"Come, boy, we must drop the old slang since we've given up the oldbusiness. These good folks are making a gentleman of you, and I won't bethe one to spoil their work. Hold on, my dears, and I'll show you howthey say good-morning in California," he added, beckoning to the littlegirls, who now came up rosy and smiling.

"Breakfast is ready, sir," said Betty, looking much relieved to findthem.

"We thought you'd run away from us," explained Bab, as both put outtheir hands to shake those extended to them.

"That would be a mean trick. But I'm going to run away with you," andMr. Brown whisked a little girl to either shoulder before they knew whathad happened, while Ben, remembering the day, with difficulty restrainedhimself from turning a series of triumphant somersaults before them allthe way to the door, where Mrs. Moss stood waiting for them.

After breakfast Ben disappeared for a short time, and returned in hisSunday suit, looking so neat and fresh that his father surveyed him withsurprise and pride as he came in full of boyish satisfaction in his trimarray.

"Here's a smart young chap! Did you take all that trouble just to go towalk with old Daddy?" asked Mr. Brown, stroking the smooth head, forthey were alone just then, Mrs. Moss and the children being up stairspreparing for church.

"I thought may be you'd like to go to meeting first," answered Ben,looking up at him with such a happy face that it was hard to refuse anything. "I'm too shabby, Sonny, else I'd go in a minute to please you."

"Miss Celia said God didn't mind poor clothes, and she took me when Ilooked worse than you do. I always go in the morning; she likes to haveme," said Ben, turning his hat about as if not quite sure what he oughtto do.

"Do you want to go?" asked his father in a tone of surprise.

"I want to please her, if you don't mind. We could have our tramp thisafternoon."

"I haven't been to meeting since mother died, and it don't seem to comeeasy, though I know I ought to, seeing I'm alive and here," and Mr.Brown looked soberly out at the lovely autumn world as if glad to be init after his late danger and pain.

"Miss Celia said church was a good place to take our troubles, and to bethankful in. I went when I thought you were dead, and now I'd love to gowhen I've got my Daddy safe again."

No one saw him, so Ben could not resist giving his father a sudden hug,which was warmly returned as the man said earnestly,--

"I'll go, and thank the Lord hearty for giving me back my boy better'n Ileft him!"

For a minute nothing was heard but the loud tick of the old clock and amournful whine front Sancho, shut up in the shed lest he should go tochurch without an invitation.

Then, as steps were heard on the stairs, Mr. Brown caught up his hat,saying hastily,--

"I ain't fit to go with them, you tell 'm, and I'll slip into a backseat after folks are in. I know the way." And, before Ben could reply,he was gone. Nothing was seen of him along the way, but he saw thelittle party, and rejoiced again over his boy, changed in so many waysfor the better; for Ben was the one thing which had kept his heart softthrough all the trials and temptations of a rough life.

"I promised Mary I'd do my best for the poor baby she had to leave, andI tried; but I guess a better friend than I am has been raised up forhim when he needed her most. It won't hurt me to follow him in thisroad," thought Mr. Brown, as he came out into the highway from hisstroll "across-lots," feeling that it would be good for him to stay inthis quiet place, for his own as well as his son's sake.

The Bell had done ringing when he reached the green, but a single boysat on the steps and rail to meet him, saying, with a reproachful look,--

"I wasn't going to let you be alone, and have folks think I was ashamedof my father. Come, Daddy, we'll sit together."

So Ben led his father straight to the Squire's pew, and sat beside himwith a face so full of innocent pride and joy, that people would havesuspected the truth if he had not already told many of them. Mr. Brown,painfully conscious of his shabby coat, was rather "taken aback," as heexpressed it; but the Squire's shake of the hand, and Mrs. Allen'sgracious nod enabled him to face the eyes of the interestedcongregation, the younger portion of which stared steadily at him allsermon time, in spite of paternal frowns and maternal tweakings in therear.

But the crowning glory of the day came after church, when the Squiresaid to Ben, and Sam heard him,--

"I've got a letter for you from Miss Celia. Come home with me, and bringyour father. I want to talk to him."

The boy proudly escorted his parent to the old carry-all, and, tuckinghimself in behind with Mrs. Allen, had the satisfaction of seeing theslouched felt hat side by side with the Squire's Sunday beaver in front,as they drove off at such an unusually smart pace, it was evident thatDuke knew there was a critical eye upon him. The interest taken in thefather was owing to the son at first; but, by the time the story wastold, old Ben had won friends for himself not only because of themisfortunes which he had evidently borne in a manly way, but because ofhis delight in the boy's improvement, and the desire he felt to turn hishand to any honest work, that he might keep Ben happy and contented inthis good home.

"I'll give you a line to Towne. Smithers spoke well of you, and yourown ability will be the best recommendation," said the Squire, as heparted from them at his door, having given Ben the letter.

Miss Celia had been gone a fortnight, and every one was longing to haveher back. The first week brought Ben a newspaper, with a crinkly linedrawn round the marriages to attract attention to that spot, and one wasmarked by a black frame with a large hand pointing at it from themargin. Thorny sent that; but the next week came a parcel for Mrs. Moss,and in it was discovered a box of wedding cake for every member of thefamily, including Sancho, who ate his at one gulp, and chewed up thelace paper which covered it. This was the third week; and, as if therecould not be happiness enough crowded into it for Ben, the letter heread on his way home told him that his dear mistress was coming back onthe following Saturday. One passage particularly pleased him,--

"I want the great gate opened, so that the new master may go in thatway. Will you see that it is done, and all made neat afterward? Randawill give you the key, and you may have out all your flags if you like,for the old place cannot look too gay for this home-coming."

Sunday though it was, Ben could not help waving the letter over his headas he ran in to tell Mrs. Moss the glad news, and begin at once to planthe welcome they would give Miss Celia, for he never called her anything else.

During their afternoon strol

l in the mellow sunshine, Ben continued totalk of her, never tired of telling about his happy summer under herroof. And Mr. Brown was never weary of hearing, for every hour showedhim more plainly what a lovely miracle her gentle words had wrought, andevery hour increased his gratitude, his desire to return the kindness insome humble way. He had his wish, and did his part handsomely when heleast expected to have a chance.

On Monday he saw Mr. Towne, and, thanks to the Squire's good word, wasengaged for a month on trial, making himself so useful that it was soonevident he was the right man in the right place. He lived on the hill,but managed to get down to the little brown house in the evening for aword with Ben, who just now was as full of business as if the Presidentand his Cabinet were coming.

Every thing was put in apple-pie order in and about the old house; thegreat gate, with much creaking of rusty hinges and some clearing away ofrubbish, was set wide open, and the first creature who entered it wasSancho, solemnly dragging the dead mullein which long ago had grownabove the keyhole. October frosts seemed to have spared some of thebrightest leaves for this especial occasion; and on Saturday the archedgate-way was hung with gay wreaths, red and yellow sprays strewed theflags, and the porch was a blaze of color with the red woodbine, thatwas in its glory when the honeysuckle was leafless.

Fortunately it was a half-holiday, so the children could trim andchatter to their heart's content, and the little girls ran aboutsticking funny decorations where no one would ever think of looking forthem. Ben was absorbed in his flags, which were sprinkled all down theavenue with a lavish display, suggesting several Fourth of Julys rolledinto one. Mr. Brown had come to lend a hand, and did so mostenergetically, for the break-neck things he did with his son during thedecoration fever would have terrified Mrs. Moss out of her wits, if shehad not been in the house giving last touches to every room, while Randaand Katy set forth a sumptuous tea.

All was going well, and the train would be due in an hour, when lucklessBab nearly turned the rejoicing into mourning, the feast into ashes. Sheheard her mother say to Randa, "There ought to be a fire in every room,it looks so cheerful, and the air is chilly spite of the sunshine;" and,never waiting to hear the reply that some of the long-unused chimneyswere not safe till cleaned, off went Bab with an apron full of oldshingles, and made a roaring blaze in the front room fire-place, whichwas of all others the one to be let alone, as the flue was out of order.

Charmed with the brilliant light and the crackle of the tindery fuel,Miss Bab refilled her apron, and fed the fire till the chimney began torumble ominously, sparks to fly out at the top, and soot and swallows'nests to come tumbling down upon the hearth. Then, scared at what shehad done, the little mischief-maker hastily buried her fire, swept upthe rubbish, and ran off, thinking no one would discover her prank ifshe never told.

Everybody was very busy, and the big chimney blazed and rumbledunnoticed till the cloud of smoke caught Ben's eye as he festooned hislast effort in the flag line, part of an old sheet with the words"Father has come!" in red cambric letters half a foot long sewed uponit.

"Hullo! I do believe they've got up a bonfire, without asking my leave.Miss Celia never would let us, because the sheds and roofs are so oldand dry; I must see about it. Catch me, Daddy, I'm coming down!" criedBen, dropping out of the elm with no more thought of where he mightlight than a squirrel swinging from bough to bough.

His father caught him, and followed in haste as his nimble-footed sonraced up the avenue, to stop in the gate-way, frightened at the prospectbefore him, for falling sparks had already kindled the roof here andthere, and the chimney smoked and roared like a small volcano, whileKaty's wails and Randa's cries for water came from within.

"Up there with wet blankets, while I get out the hose!" cried Mr. Brown,as he saw at a glance what the danger was.

Ben vanished; and, before his father got the garden hose rigged, he wason the roof with a dripping blanket over the worst spot. Mrs. Moss hadher wits about her in a minute, and ran to put in the fireboard, andstop the draught. Then, stationing Randa to watch that the fallingcinders did no harm inside, she hurried off to help Mr. Brown, who mightnot know where things were. But he had roughed it so long, that he wasthe man for emergencies, and seemed to lay his hand on whatever wasneeded, by a sort of instinct. Finding that the hose was too short toreach the upper part of the roof, he was on the roof in a jiffy with twopails of water, and quenched the most dangerous spots before much harmwas done.

This he kept up till the chimney burned itself out, while Ben dodgedabout among the gables with a watering pot, lest some stray sparksshould be over-looked, and break out afresh.

While they worked there, Betty ran to and fro with a dipper of water,trying to help; and Sancho barked violently, as if he objected to thissort of illumination. But where was Bab, who revelled in flurries? Noone missed her till the fire was out, and the tired, sooty people met totalk over the danger just escaped.

"Poor Miss Celia wouldn't have had a roof over her head, if it hadn'tbeen for you, Mr. Brown," said Mrs. Moss, sinking into a kitchen chair,pale with the excitement.

"It would have burnt lively, but I guess it's all right now. Keep an eyeon the roof, Ben, and I'll step up garret and see if all's safe there.Didn't you know that chimney was foul, ma'am?" asked the man, as hewiped the perspiration off his grimy face.

"Randa said it was, and I 'in surprised she made a fire there," beganMrs. Moss, looking at the maid, who just then came in with a pan full ofsoot.

"Bless you, ma'am, I never thought of such a thing, nor Katy neither.That naughty Bab must have done it, and so don't dar'st to showherself," answered the irate Randa, whose nice room was in a mess.

"Where is the child?" asked her mother; and a hunt was immediatelyinstituted by Betty and Sancho, while the elders cleared up.

Anxious Betty searched high and low, called and cried, but all in vain;and was about to sit down in despair, when Sancho made a bolt into hisnew kennel and brought out a shoe with a foot in it while a dolefulsqueal came from the straw within.

"Oh, Bab, how could you do it? Ma was frightened dreadfully," saidBetty, gently tugging at the striped leg, as Sancho poked his head infor another shoe.

"Is it all burnt up?" demanded a smothered voice from the recesses ofthe kennel.

"Only pieces of the roof. Ben and his father put it out, and I helped,"answered Betty, cheering up a little as she recalled her nobleexertions.

"What do they do to folks who set houses afire?" asked the voice again.

"I don't know; but you needn't be afraid, there isn't much harm done, Iguess, and Miss Celia will forgive you, she's so good."

"Thorny won't; he calls me a 'botheration,' and I guess I am," mournedthe unseen culprit, with sincere contrition.

"I'll ask him; he is always good to me. They will be here pretty soon,so you'd better come out and be made tidy," suggested the comforter.

"I never can come out, for every one will hate me," sobbed Bab among thestraw, as she pulled in her foot, as if retiring for ever from anoutraged world.

"Ma won't, she's too busy cleaning up; so it's a good time to come.Let's run home, wash our hands, and be all nice when they see us. I'lllove you, no matter what anybody else does," said Betty, consoling thepoor little sinner, and proposing the sort of repentance most likely tofind favor in the eyes of the agitated elders.

"P'raps I'd better go home, for Sanch will want his bed," and Bab gladlyavailed herself of that excuse to back out of her refuge, a verycrumpled, dusty young lady, with a dejected face and much straw stickingin her hair.

Betty led her sadly away, for she still protested that she never shoulddare to meet the offended public again; but in fifteen minutes bothappeared in fine order and good spirits, and naughty Bab escaped alecture for the time being, as the train would soon be due.

At the first sound of the car whistle every one turned good-natured asif by magic, and flew to the gate smiling as if all mishaps wereforgiven and forgotten. Mrs. Moss, however, slipped qu

ietly away, andwas the first to greet Mrs. Celia as the carriage stopped at theentrance of the avenue, so that the luggage might go in by way of thelodge.

"We will walk up and you shall tell us the news as we go, for I see youhave some," said the young lady, in her friendly manner, when Mrs. Mosshad given her welcome and paid her respects to the gentleman who shookhands in a way that convinced her he was indeed what Thorny called him,"regularly jolly," though he was a minister.

That being exactly what she came for, the good woman told her tidings asrapidly as possible, and the new-comers were so glad to hear of Ben'shappiness they made very light of Bab's bonfire, though it had nearlyburnt their house down.

"We won't say a word about it, for every one must be happy to-day," saidMr. George, so kindly that Mrs. Moss felt a load taken off her heart atonce.

"Bab was always teasing me for fireworks, but I guess she has had enoughfor the present," laughed Thorny, who was gallantly escorting Bab'smother up the avenue.

"Every one is so kind! Teacher was out with the children to cheer us aswe passed, and here you all are making things pretty for me," said Mrs.Celia, smiling with tears in her eyes, as they drew near the great gate,which certainly did present an animated if not an imposing appearance.

Randa and Katy stood on one side, all in their best, bobbing delightedcourtesies; Mr. Brown, half hidden behind the gate on the other side,was keeping Sancho erect, so that he might present arms promptly whenthe bride appeared. As flowers were scarce, on either post stood a rosylittle girl clapping her hands, while out from the thicket of red andyellow boughs, which made a grand bouquet in the lantern frame, cameBen's head and shoulders, as he waved his grandest flag with its goldpaper "Welcome Home!" on a blue ground.

"Isn't it beautiful!" cried Mrs. Celia, throwing kisses to the children,shaking hands with her maids, and glancing brightly at the stranger whowas keeping Sanch quiet.

"Most people adorn their gate-posts with stone balls, vases, orgriffins; your living images are a great improvement, love, especiallythe happy boy in the middle," said Mr. George, eying Ben with interest,as he nearly tumbled overboard, top-heavy with his banner.

"You must finish what I have only begun," answered Celia, adding gaylyas Sancho broke loose and came to offer both his paw and hiscongratulations. "Sanch, introduce your master, that I may thank him forcoming back in time to save my old house."

"If I'd saved a dozen it wouldn't have half paid for all you've done formy boy, ma'am," answered Mr. Brown, bursting out from behind the gatequite red with gratitude and pleasure.

"I loved to do it, so please remember that this is still his home tillyou make one for him. Thank God, he is no longer fatherless!" and hersweet face said even more than her words as the white hand cordiallyshook the brown one with a burn across the back.

"Come on, sister. I see the tea-table all ready, and I'm awfullyhungry," interrupted Thorny, who had not a ray of sentiment about him,though very glad Ben had got his father back again.

"Come over, by-and-by, little friends, and let me thank you for yourpretty welcome,--it certainly is a warm one;" and Mrs. Celia glancedmerrily from the three bright faces above her to the old chimney, whichstill smoked sullenly.

"Oh, don't!" cried Bab, hiding her face.

"She didn't mean to," added Betty, pleadingly.

"Three cheers for the bride!" roared Ben, dipping his flag, as leaningon her husband's arm his dear mistress passed under the gay arch, alongthe leaf-strewn walk, over the threshold of the house which was to beher happy home for many years.

The closed gate where the lonely little wanderer once lay was always tostand open now, and the path where children played before was free toall comers, for a hospitable welcome henceforth awaited rich and poor,young and old, sad and gay, Under the Lilacs.

Little Women

Little Women Good Wives

Good Wives Jo's Boys

Jo's Boys Under the Lilacs

Under the Lilacs The Mysterious Key and What It Opened

The Mysterious Key and What It Opened The Inheritance

The Inheritance Eight Cousins

Eight Cousins Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill

Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill Marjorie's Three Gifts

Marjorie's Three Gifts Little Men

Little Men The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story

The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story Rose in Bloom

Rose in Bloom Shawl-Straps

Shawl-Straps Hospital Sketches

Hospital Sketches Flower Fables

Flower Fables An Old-Fashioned Girl

An Old-Fashioned Girl The Candy Country

The Candy Country Jack and Jill

Jack and Jill A Garland for Girls

A Garland for Girls The Annotated Little Women

The Annotated Little Women A Classic Christmas

A Classic Christmas A Merry Christmas

A Merry Christmas Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Little Vampire Women

Little Vampire Women