- Home

- Louisa May Alcott

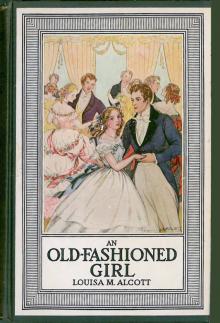

An Old-Fashioned Girl Page 23

An Old-Fashioned Girl Read online

Page 23

"Willy likes Flossy best, so stop crying and come right along, you naughty child."

As poor little Dido was jerked away by the unsympathetic maid, and Purple-gaiters essayed in vain to plead his cause, Polly said to herself, with a smile and a sigh; "How early the old story begins!"

It seemed as if the spring weather had brought out all manner of tender things beside fresh grass and the first dandelions, for as she went down the street Polly kept seeing different phases of the sweet old story which she was trying to forget.

At a street corner, a black-eyed school-boy was parting from a rosy-faced school-girl, whose music roll he was reluctantly surrendering.

"Don't you forget, now," said the boy, looking bashfully into the bright eyes that danced with pleasure as the girl blushed and smiled, and answered reproachfully; "Why, of course I shan't!"

"That little romance runs smoothly so far; I hope it may to the end," said Polly heartily as she watched the lad tramp away, whistling as blithely as if his pleasurable emotions must find a vent, or endanger the buttons on the round jacket; while the girl pranced on her own doorstep, as if practising for the joyful dance which she had promised not to forget.

A little farther on Polly passed a newly engaged couple whom she knew, walking arm in arm for the first time, both wearing that proud yet conscious look which is so delightful to behold upon the countenances of these temporarily glorified beings.

"How happy they seem; oh, dear!" said Polly, and trudged on, wondering if her turn would ever come and fearing that it was impossible.

A glimpse of a motherly-looking lady entering a door, received by a flock of pretty children, who cast themselves upon mamma and her parcels with cries of rapture, did Polly good; and when, a minute after she passed a gray old couple walking placidly together in the sunshine, she felt better still, and was glad to see such a happy ending to the romance she had read all down the street.

As if the mischievous little god wished to take Polly at a disadvantage, or perhaps to give her another chance, just at that instant Mr. Sydney appeared at her side. How he got there was never very clear to Polly, but there he was, flushed, and a little out of breath, but looking so glad to see her that she had n't the heart to be stiff and cool, as she had fully intended to be when they met.

"Very warm, is n't it?" he said when he had shaken hands and fallen into step, just in the old way.

"You seem to find it so." And Polly laughed, with a sudden sparkle in her eyes. She really could n't help it, it was so pleasant to see him again, just when she was feeling so lonely.

"Have you given up teaching the Roths?" asked Sydney, changing the subject.

"No."

"Do you go as usual?"

"Yes."

"Well, it 's a mystery to me how you get there."

"As much as it is to me how you got here so suddenly."

"I saw you from the Shaws' window and took the liberty of running after you by the back street," he said, laughing.

"That is the way I get to the Roths," answered Polly. She did not mean to tell, but his frankness was so agreeable she forgot herself.

"It 's not nearly so pleasant or so short for you as the park."

"I know it, but people sometimes get tired of old ways and like to try new ones."

Polly did n't say that quite naturally, and Sydney gave her a quick look, as he asked;

"Do you get tired of old friends, too, Miss Polly?"

"Not often; but " And there she stuck, for the fear of being ungrateful or unkind made her almost hope that he would n't take the hint which she had been carefully preparing for him.

There was a dreadful little pause, which Polly broke by saying abruptly; "How is Fan?"

"Dashing, as ever. Do you know I 'm rather disappointed in Fanny, for she don't seem to improve with her years," said Sydney, as if he accepted the diversion and was glad of it.

"Ah, you never see her at her best. She puts on that dashing air before people to hide her real self. But I know her better; and I assure you that she does improve; she tries to mend her faults, though she won't own it, and will surprise you some day, by the amount of heart and sense and goodness she has got."

Polly spoke heartily now, and Sydney looked at her as if Fanny's defender pleased him more than Fanny's defence.

"I 'm very glad to hear it, and willingly take your word for it. Everybody shows you their good side, I think, and that is why you find the world such a pleasant place."

"Oh, but I don't! It often seems like a very hard and dismal place, and I croak over my trials like an ungrateful raven."

"Can't we make the trials lighter for you?"

The voice that put the question was so very kind, that Polly dared not look up, because she knew what the eyes were silently saying.

"Thank you, no. I don't get more tribulation than is good for me, I fancy, and we are apt to make mistakes when we try to dodge troubles."

"Or people," added Sydney in a tone that made Polly color up to her forehead.

"How lovely the park looks," she said, in great confusion.

"Yes, it 's the pleasantest walk we have; don't you think so?" asked the artful young man, laying a trap, into which Polly immediately fell.

"Yes, indeed! It 's always so refreshing to me to see a little bit of the country, as it were, especially at this season."

Oh, Polly, Polly, what a stupid speech to make, when you had just given him to understand that you were tired of the park! Not being a fool or a cox-comb, Sydney put this and that together, and taking various trifles into the account, he had by this time come to the conclusion that Polly had heard the same bits of gossip that he had, which linked their names together, that she did n't like it, and tried to show she did n't in this way. He was quicker to take a hint than she had expected, and being both proud and generous, resolved to settle the matter at once, for Polly's sake as well as his own. So, when she made her last brilliant remark, he said quietly, watching her face keenly all the while; "I thought so; well, I 'm going out of town on business for several weeks, so you can enjoy your 'little bit of country' without being annoyed by me."

"Annoyed? Oh, no!" cried Polly earnestly; then stopped short, not knowing what to say for herself. She thought she had a good deal of the coquette in her, and I 've no doubt that with time and training she would have become a very dangerous little person, but now she was far too transparent and straightforward by nature even to tell a white lie cleverly. Sydney knew this, and liked her for it, but he took advantage of it, nevertheless by asking suddenly; "Honestly, now, would n't you go the old way and enjoy it as much as ever, if I was n't anywhere about to set the busybodies gossiping?"

"Yes," said Polly, before she could stop herself, and then could have bitten her tongue out for being so rude. Another awful pause seemed impending, but just at that moment a horseman clattered by with a smile and a salute, which caused Polly to exclaim, "Oh, there 's Tom!" with a tone and a look that silenced the words hovering on Sydney's lips, and caused him to hold out his hand with a look which made Polly's heart flutter then and ache with pity for a good while afterward, though he only said, "Good by, Polly."

He was gone before she could do anything but look up at him with a remorseful face, and she walked on, feeling that the first and perhaps the only lover she would ever have, had read his answer and accepted it in silence. She did not know what else he had read, and comforted herself with the thought that he did not care for her very much, since he took the first rebuff so quickly.

Polly did not return to her favorite walk till she learned from Minnie that "Uncle" had really left town, and then she found that his friendly company and conversation was what had made the way so pleasant after all. She sighed over the perversity of things in general, and croaked a little over her trials in particular, but on the whole got over her loss better than she expected, for soon she had other sorrows beside her own to comfort, and such work does a body more good than floods of regretful tears, or hours of s

entimental lamentation.

She shunned Fanny for a day or two, but gained nothing by it, for that young lady, hearing of Sydney's sudden departure, could not rest till she discovered the cause of it, and walked in upon Polly one afternoon just when the dusk made it a propitious hour for tender confidences.

"What have you been doing with yourself lately?" asked Fanny, composing herself, with her back toward the rapidly waning light.

"Wagging to and fro as usual. What's the news with you?" answered Polly, feeling that something was coming and rather glad to have it over and done with.

"Nothing particular. Trix treats Tom shamefully, and he bears it like a lamb. I tell him to break his engagement, and not be worried so; but he won't, because she has been jilted once and he thinks it 's such a mean thing to do."

"Perhaps she 'll jilt him."

"I 've no doubt she will, if anything better comes along. But Trix is getting pass,e, and I should n't wonder if she kept him to his word, just out of perversity, if nothing else."

"Poor Tom, what a fate!" said Polly with what was meant to be a comical groan; but it sounded so tragical that she saw it would n't pass, and hastened to hide the failure by saying, with a laugh, "If you call Trix pass,e at twenty-three, what shall we all be at twenty-five?" "Utterly done with, and laid upon the shelf. I feel so already, for I don't get half the attention I used to have, and the other night I heard Maud and Grace wondering why those old girls 'did n't stay at home, and give them a chance.' "

"How is Maudie?"

"Pretty well, but she worries me by her queer tastes and notions. She loves to go into the kitchen and mess, she hates to study, and said right before the Vincents that she should think it would be great fun to be a beggar-girl, to go round with a basket, it must be so interesting to see what you 'd get."

"Minnie said the other day she wished she was a pigeon so she could paddle in the puddles and not fuss about rubbers."

"By the way, when is her uncle coming back?" asked Fanny, who could n't wait any longer and joyfully seized the opening Polly made for her.

"I 'm sure I don't know."

"Nor care, I suppose, you hard-hearted thing."

"Why, Fan, what do you mean?"

"I 'm not blind, my dear, neither is Tom, and when a young gentleman cuts a call abruptly short, and races after a young lady, and is seen holding her hand at the quietest corner of the park, and then goes travelling all of a sudden, we know what it means if you don't."

"Who got up that nice idea, I should like to know?" demanded Polly, as Fanny stopped for breath.

"Now don't be affected, Polly, but just tell me, like a dear, has n't he proposed?"

"No, he has n't."

"Don't you think he means to?"

"I don't think he 'll ever say a word to me."

"Well, I am surprised!" And Fanny drew a long breath, as if a load was off her mind.

Then she added in a changed tone: "But don't you love him, Polly?"

"No."

"Truly?"

"Truly, Fan."

Neither spoke for a minute, but the heart of one of them beat joyfully and the dusk hid a very happy face.

"Don't you think he cared for you, dear?" asked Fanny, presently. "I don't mean to be prying, but I really thought he did."

"That 's not for me to say, but if it is so, it 's only a passing fancy and he 'll soon get over it."

"Do tell me all about it; I 'm so interested, and I know something has happened, I hear it in your voice, for I can't see your face."

"Do you remember the talk we once had after reading one of Miss Edgeworth's stories about not letting one's lovers come to a declaration if one did n't love them?"

"Yes."

"And you girls said it was n't proper, and I said it was honest, anyway. Well, I always meant to try it if I got a chance, and I have. Mind you, I don't say Mr. Sydney loved me, for he never said so, and never will, now, but I did fancy he rather liked me and might do more if I did n't show him that it was of no use."

"And you did?" cried Fanny, much excited.

"I just gave him a hint and he took it. He meant to go away before that, so don't think his heart is broken, or mind what silly tattlers say. I did n't like his meeting me so much and told him so by going another way. He understood, and being a gentleman, made no fuss. I dare say he thought I was a vain goose, and laughed at me for my pains, like Churchill in 'Helen.' "

"No, he would n't; He 'd like it and respect you for doing it. But, Polly, it would have been a grand thing for you."

"I can't sell myself for an establishment."

"Mercy! What an idea!"

"Well, that 's the plain English of half your fashionable matches. I 'm 'odd,' you know, and prefer to be an independent spinster and teach music all my days."

"Ah, but you won't. You were made for a nice, happy home of your own, and I hope you

'll get it, Polly, dear," said Fanny warmly, feeling so grateful to Polly, that she found it hard not to pour out all her secret at once.

"I hope I may; but I doubt it," answered Polly in a tone that made Fanny wonder if she, too, knew what heartache meant.

"Something troubles you, Polly, what is it? Confide in me, as I do in you," said Fanny tenderly, for all the coldness she had tried to hide from Polly, had melted in the sudden sunshine that had come to her.

"Do you always?" asked her friend, leaning forward with an irresistible desire to win back the old-time love and confidence, too precious to be exchanged for a little brief excitement or the barren honor of "bagging a bird," to use Trix's elegant expression.

Fanny understood it then, and threw herself into Polly's arms, crying, with a shower of grateful tears; "Oh, my dear! my dear! did you do it for my sake?"

And Polly held her close, saying in that tender voice of hers, "I did n't mean to let a lover part this pair of friends if I could help it."

15. Breakers Ahead

GOING into the Shaws' one evening, Polly found Maud sitting on the stairs, with a troubled face.

"Oh, Polly, I 'm so glad you 've come!" cried the little girl, running to hug her.

"What's the matter, deary?"

"I don't know; something dreadful must have happened, for mamma and Fan are crying together upstairs, papa is shut up in the library, and Tom is raging round like a bear, in the dining-room."

"I guess it is n't anything very bad. Perhaps mamma is sicker than usual, or papa worried about business, or Tom in some new scrape. Don't look so frightened, Maudie, but come into the parlor and see what I 've got for you," said Polly, feeling that there was trouble of some sort in the air, but trying to cheer the child, for her little face was full of a sorrowful anxiety, that went to Polly's heart.

"I don't think I can like anything till I know what the matter is," answered Maud. "It 's something horrid, I 'm sure, for when papa came home, he went up to mamma's room, and talked ever so long, and mamma cried very loud, and when I tried to go in, Fan would n't let me, and she looked scared and strange. I wanted to go to papa when he came down, but the door was locked, and he said, 'Not now, my little girl,' and then I sat here waiting to see what would happen, and Tom came home. But when I ran to tell him, he said, 'Go away, and don't bother,' and just took me by the shoulders and put me out. Oh, dear! everything is so queer and horrid, I don't know what to do."

Maud began to cry, and Polly sat down on the stairs beside her, trying to comfort her, while her own thoughts were full of a vague fear. All at once the dining-room door opened, and Tom's head appeared. A single glance showed Polly that something was the matter, for the care and elegance which usually marked his appearance were entirely wanting. His tie was under one ear, his hair in a toss, the cherished moustache had a neglected air, and his face an expression both excited, ashamed, and distressed; even his voice betrayed disturbance, for instead of the affable greeting he usually bestowed upon the young lady, he seemed to have fallen back into the bluff tone of his boyish days, and all he said was, "Hull

o, Polly."

"How do you do?" answered Polly.

"I 'm in a devil of a mess, thank you; send that chicken up stairs, and come in and hear about it." he said, as if he had been longing to tell some one, and welcomed prudent Polly as a special providence.

"Go up, deary, and amuse yourself with this book, and these ginger snaps that I made for you, there 's a good child," whispered Polly, as Maud rubbed away her tears, and stared at Tom with round, inquisitive eyes.

"You 'll tell me all about it, by and by, won't you?" she whispered, preparing to obey.

"If I may," answered Polly.

Maud departed with unexpected docility, and Polly went into the dining-room, where Tom was wandering about in a restless way. If he had been "raging like a bear," Polly would n't have cared, she was so pleased that he wanted her, and so glad to be a confidante, as she used to be in the happy old days, that she would joyfully have faced a much more formidable person than reckless Tom.

"Now, then, what is it?" she said, coming straight to the point.

"Guess."

"You 've killed your horse racing."

"Worse than that."

"You are suspended again."

"Worse than that."

"Trix has run away with somebody," cried Polly, with a gasp.

"Worse still."

"Oh, Tom, you have n't horse whipped or shot any one?"

"Came pretty near blowing my own brains out but you see I did n't."

"I can't guess; tell me, quick."

"Well, I 'm expelled."

Tom paused on the rug as he gave the answer, and looked at Polly to see how she took it. To his surprise she seemed almost relieved, and after a minute silence, said, soberly,

"That 's bad, very bad; but it might have been worse."

"It is worse;" and Tom walked away again with a despairing sort of groan.

"Don't knock the chairs about, but come and sit down, and tell me quietly."

Little Women

Little Women Good Wives

Good Wives Jo's Boys

Jo's Boys Under the Lilacs

Under the Lilacs The Mysterious Key and What It Opened

The Mysterious Key and What It Opened The Inheritance

The Inheritance Eight Cousins

Eight Cousins Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill

Eight Cousins; Or, The Aunt-Hill Marjorie's Three Gifts

Marjorie's Three Gifts Little Men

Little Men The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story

The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation: A Christmas Story Rose in Bloom

Rose in Bloom Shawl-Straps

Shawl-Straps Hospital Sketches

Hospital Sketches Flower Fables

Flower Fables An Old-Fashioned Girl

An Old-Fashioned Girl The Candy Country

The Candy Country Jack and Jill

Jack and Jill A Garland for Girls

A Garland for Girls The Annotated Little Women

The Annotated Little Women A Classic Christmas

A Classic Christmas A Merry Christmas

A Merry Christmas Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Little Women (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Little Vampire Women

Little Vampire Women